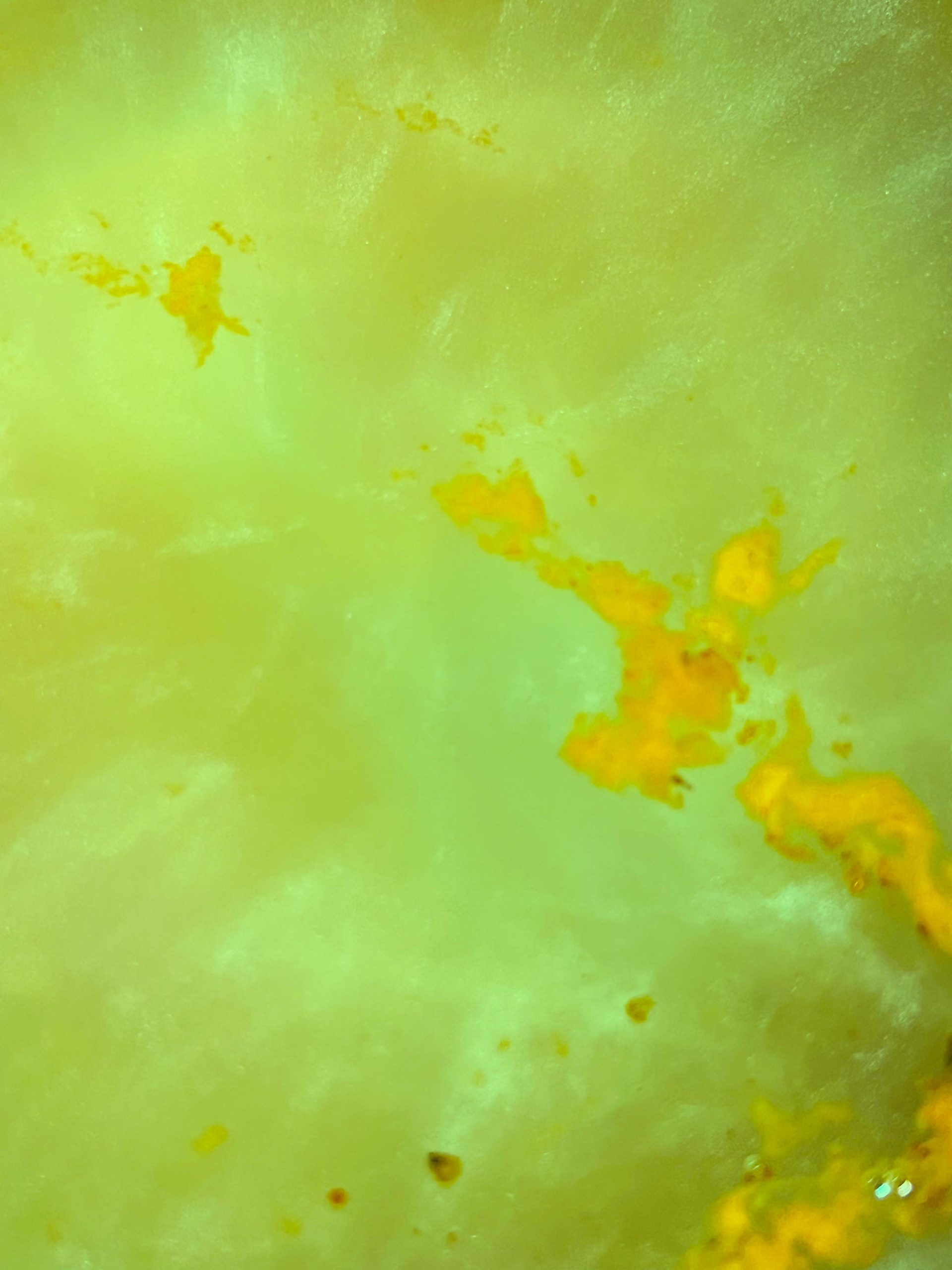

The Rat Islands – pictured at 11,000 ft – are not known for their posh lodging nor their 4 star bistros, they don’t have high speed rail or a 5G network, & as of 1 January 2025, they still have no indoor plumbing. This is bc they don’t have any permanent human residents. The only people to step foot on the islands, since the late 1970s, are a small group of dedicated farmhands that make an annual pilgrimage from 3 counties in Northern Wisconsin, 5 counties in Northern Minnesota & 1 county in Upper North Dakota’s Eastern High Prairie. In any given year, the group ranges from 35 – 140. They don’t come for the invigorating salt bath in waters that regularly dip into the single digits Fahrenheit; and they don’t come for the Frozen Yoga retreat w/ Elephant seals (not recommended). No, these agrarian guests come for 1 reason, harvest. And what, you may ask, would they be harvesting on islands in the middle of the Bering Sea? Torpical fruit. No, not a typo. Not tropical, that’s in the tropics. Torpical, in the torpics – a microclimate that benefits from both the heat of large magma pools bubbling less than 100 meters below the rocky earth & the warm South Pacific trade-winds that maintain an ambient temperature of 82.6° F & a relative humidity of +/- 87%. The specific path of these winds, which originate just northeast of Tonga & break away from the South Pacific Gyre 15 km East of Bora Bora, provides the basis for the stable conditions. The winds hop back & forth between current & countercurrent airstreams, which explains the reserve of potential energy (it can be greater than 275 trillion joules in an average stream) the wind’s accumulate over the course of the journey – anywhere from 3-6 weeks (depending on the saturation levels of algae blooms between Palau & Kamaishi, Japan), and provide both the moisture & warmth required for the cultivation of torpical fruit. The Pickers of Torpical American Fruits Society (POTAFS – not to be confused w/ BOTRFO – the Russian counterpart) spend most of the 72 hour picking window on the Southeast Coast of Amchitka Island where the Pongo & Papple fruits are the most abundant. Once every 20 years, an unexplained phenomenon occurs. The tilt of the earth increases from 23.5° to 23.508°, for exactly 12 hours. This additional tilt affects the islands by producing just enough added heat to cause the seven Jacknut trees to flower over the next 24-36 hours. The flowers that are able to fully mature in this extremely short gestation window will bear fruit in 2-3 years time, depending on the severity of the dark season (cloudless nights can dip into the 40’s for several hours). When mature, these Jacknut fruits weigh more than 250 lbs, on average, and measure between 4 – 6 feet long and 2 -4 feet in diameter. The meat of these fruits is extremely nutritious and contains more than 30 vitamins and minerals in varying quantities as well as an abundance of amino acids and antioxidants. In years when these trees bore fruit, the seal, walrus, and rat populations boomed. There are reports from the 1870s and 1930s providing documentation of rats doubling in size from the previous year’s data and pinnipeds developing larger fins and more streamlined torsos – providing for much greater success when hunting for food. The pickers, always an astute bunch (as farm hands usually are), noticed the correlation between the Jacknut fruit ripening and the explosion of native mammal population numbers and attributes and decided to bring some Jacknuts back to their home states. That first Jacknut haul, in 1895, was a boon to the locals who got their hands on it. Lumberjacks in Minnesota and Wisconsin started felling trees at a rate three and a half times faster than before eating the fruit. And in North Dakota, recent transplants from back East, particularly the Germans and Norwegians, found they were able to clear an acre of woods and get the land ready for crops in just weeks whereas prior to this revolutionary discovery they would have spent six months in the process. Starting in the mid 1950s, pickers noticed a slight change in both the mammal populations and the volume of the average Jacknut fruit. Not knowing the cause of the abnormality they assumed it was weather related. The following harvest, the mid ’70s, saw a further decline in the species expected numbers as well as fruit volume and quality. By the mid ’90’s harvest, 5 of the 7 Jacknut fruit trees were dead and the remaining 2 had not produced any fruit. This was documented by the pickers, all 113 of them. They provided written documentation and many took pictures. Upon completion of harvest they collected several branches from each of the five dead trees and took a small sample of bark from the other two. Once back home, they sent the specimens to a pomology & food-science lab in Cincinnati Ohio. The researchers found 2 types of organic polymers that were increasingly common in certain synthetic materials (plastics). That didn’t come as a surprise but what did was the discovery of significant amounts of gamma radiation in the wood. Measurements between 1.77 – 2.13 gray were recorded in the dead limbs and the bark was found to have levels between .025 – .096. This discovery led to further testing of additional organic materials from the main island, Amchitka, and the 5 closest islands. They also tested several older Harbor Seals and 12 senior Walruses. In each specimen, a minimum of .013 gray units was found; and the oldest of all the mammals, a Walrus named Kurt, recorded .027. These animals had been living radioactive lives and didn’t seem to be out of the norm (aside from a 3rd eye here and there or an extra flipper extending from the back loin). Without going into the whole long story, additional research posits a theory that nuclear testing in the South Pacific, starting in 1946, was responsible for the 1950s subpar Jacknut crop. They believe gamma rays floated on the trade winds, spilling out here and there with an unusually high concentration being left in the area of the Rat Islands. Then, in the 1970s, the underground nuclear testing on Amchitka would have likely caused the death of the 5 Jacknut trees. How the other 2 survived nobody knows, except maybe the rats.

Several local legends benefitted from the Jacknut fruit phenomenon. And whether their careers would have turned out vastly different without this superfood no one can say for sure; but when considering the odds of stardom in any given field, it’s a safe bet that these individuals were beneficiaries of the secret power of Jacknuts. From Minnesota, Judy Garland (Grand Rapids) and Roger Maris and Bob Dylan (Hibbing) had extended family that worked on the Rat Islands. And from Wisconsin, Bud Grant’s Aunt Marge picked fruit up there for 37 years, a real trooper. North Dakota’s most famous Jacknut-touched person was Sven Olefson, who’s dad, Ole Svenfson, made the trip 3 times. Sven won the 1923 Pembina Red River Frozen Kayak race – the first, last, and only time that race was run. And while Sven went on to do great things with his life, his gravestone reads: “Here lies Sven Olefson,1903-1993, Champion of the 1923 Pembina Red River Frozen Kayak race, Loving Father & Husband, and pretty good at horseshoes” – with a post-script added about 10 years later “ski-jumped at 1924 olympics after losing bet with Thor – unofficial distance 293 meters”. You can bet the Jacknut fruit is to thank for that feat.